Games

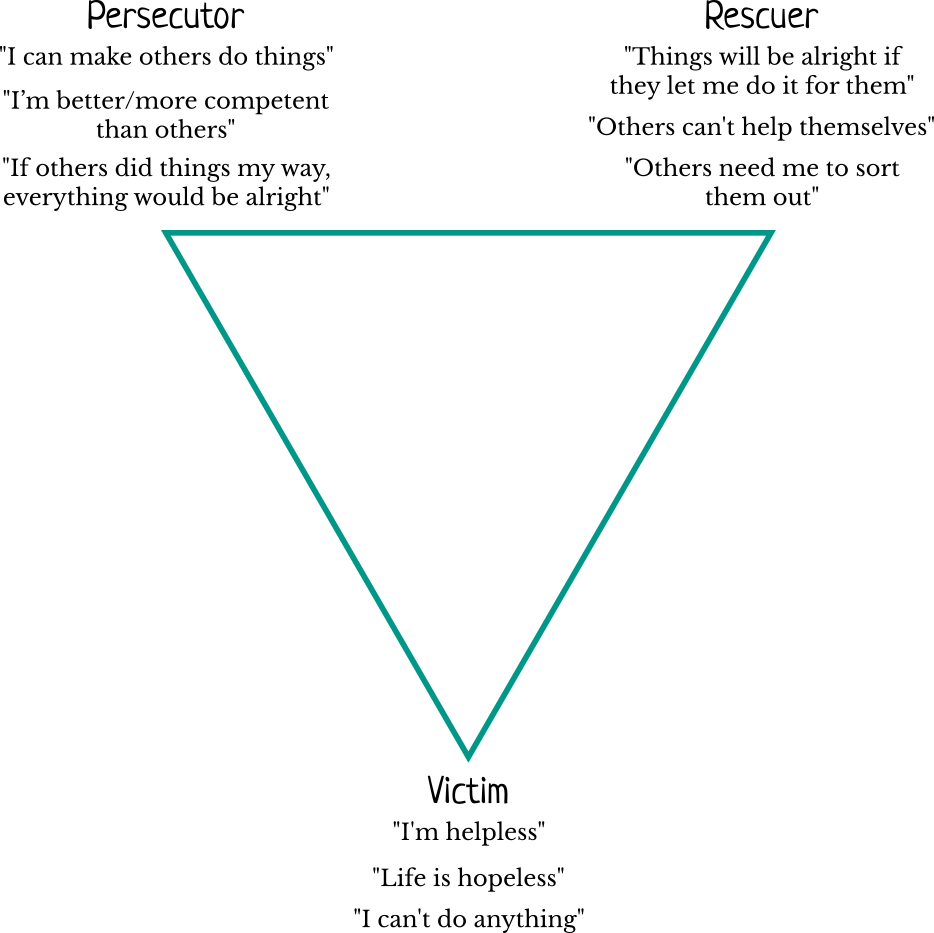

The Drama Triangle

The Drama Triangle is arguably the best known illustration of psychological game-playing. Originated by Stephen Karpman, it depicts the interaction of individuals taking on social roles of Persecutor, Rescuer or Victim. The individuals ‘switch’ their roles, which is one of the features of game-playing, and which leads eventually to a negative script ‘pay-off’. This means that a script belief or decision is confirmed, for example, ‘I don’t ever really belong’, or “Whatever I do is never good enough’ etc.

Despite the familiar engagement in game-playing roles, it is always unhealthy because it relies on discounting, engages individuals in rackets and driver behaviours and emphasises the restrictive and limiting aspects of individual script.

A good way of introducing the drama triangle to students is through viewing 'Mike's New Car' - see if you can spot the three drama triangle roles and how they switch! You can count the car as one of the characters, and if you look very closely, you will spot the Bystander.

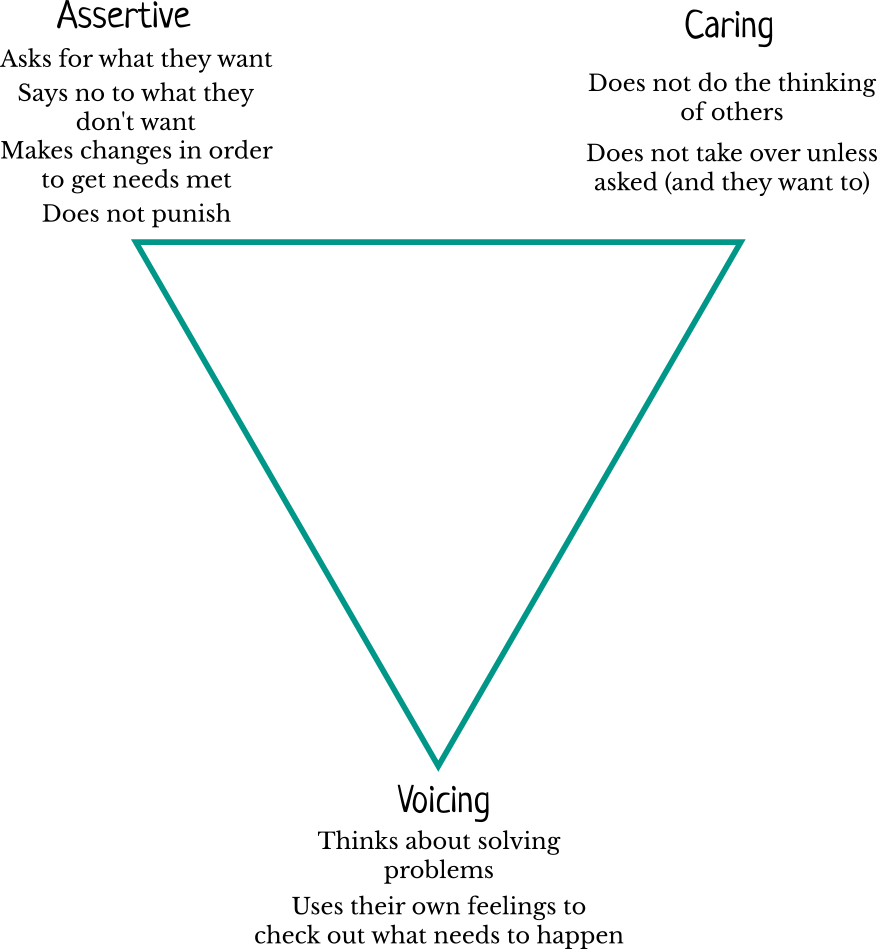

The Winners' Triangle

The Winner’s Triangle was devised by Choy in an article in which she sets out to describe what happens when things go well, despite difficulties. Her three corners relate to qualities, rather than roles and promote Adult - Adult relationships. These are intended to promote autonomous relationships and invite individuals out of scripty patterns.

One way of shifting from the drama to the winners' triangle is the use of Solution Focussed Brief Therapy questions, and examples of how these questions can encourage a more effective exchange are here.

Rackets

The term racket is used in several different ways in TA.

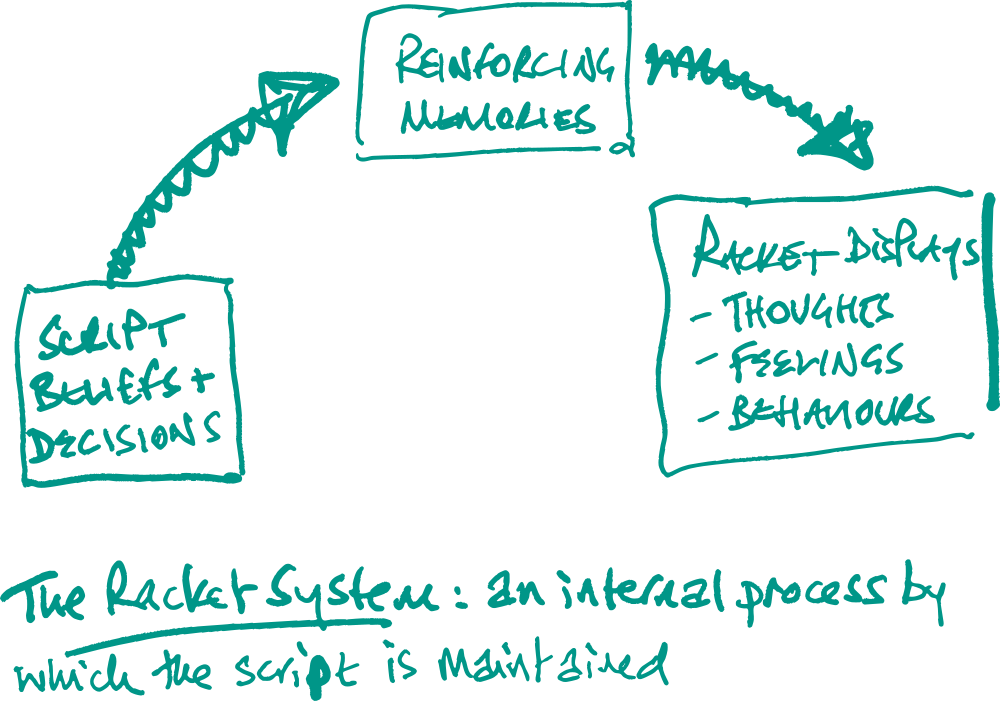

Berne used the word originally to convey the idea of how the individual sets up an internal protection racket through which they defend themselves from feeling a prohibited emotion. It becomes a habitual way of behaving and is similar to a game in terms of its recurring pattern.

It has been suggested that rackets are ways of acting that get us strokes and we only enter into a game when we don't get enough strokes from the racket behaviour. We experience our racket instead of asking for what we want, or saying what we mean and so justify our script beliefs. If that doesn’t work then we pull the switch and go for the game payoff.

Rackets are also described as substitute feelings - or preferably, 'racket feeling'. We experience then rather than the sadness, anger, joy or fear that we have learnt is too dangerous to feel. For example, a little girl learns that it is not OK to show anger, shout and have a tantrum. So girls may learn to cry when the experience anger - or 'be good about it' - and then gradually lose the sense of anger and instead become accustomed to the strokes associated with crying.

Conversely boys may learn that it is not OK for them to show sadness or fear. Instead they develop a different form of protection and display anger. The boy looks for strokes around power and strength as a way of avoiding recognising the prohibited feeling.

The Racket System refers to the specific concept of a self-reinforcing process that maintains the individual’s script beliefs and decisions.

Discounting, Accounting & Passivity

Discounting refers to how individuals – and groups – can either ignore or play down the value of something in the ‘here and now’ reality. What this means in practice is that individuals discount something about themselves, about others and/or the situation.

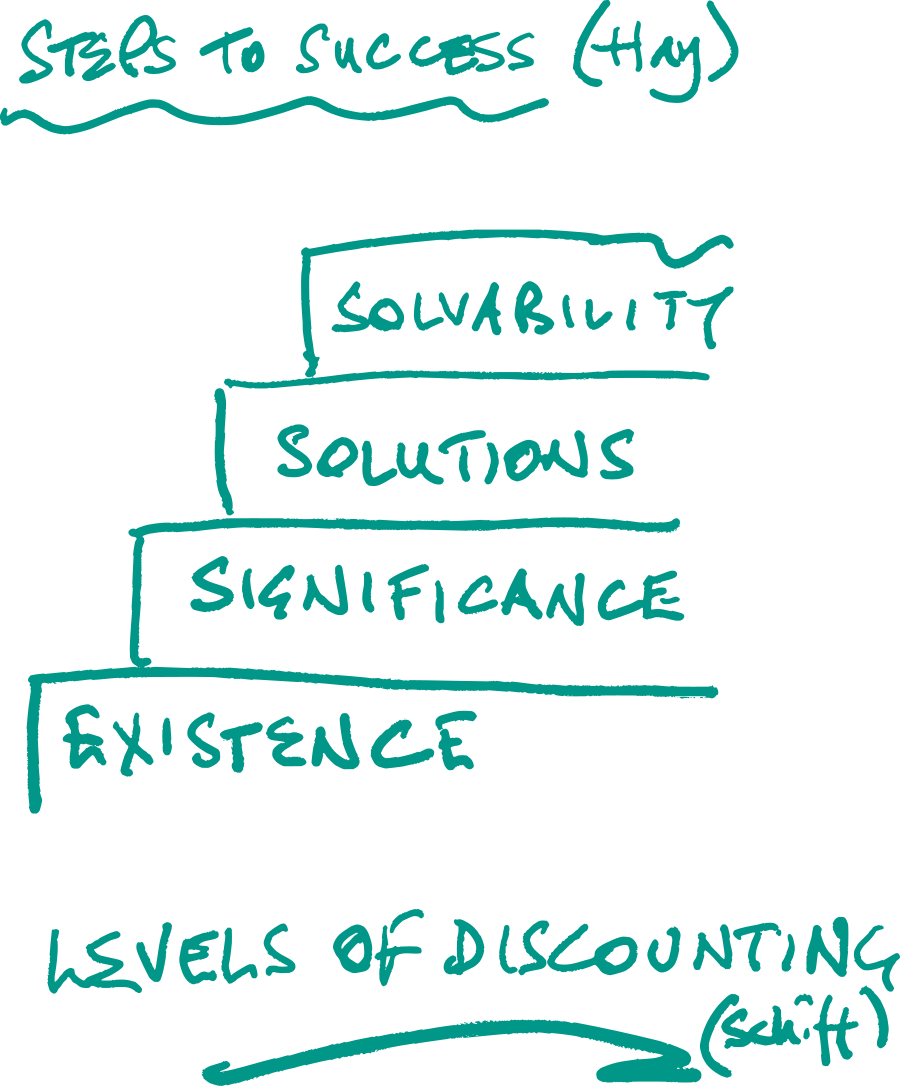

There are four ascending levels of discounting:

-

Discounting existence of a problem, for example:

- ‘There’s no problem about me smoking’

- 'We all get along like one happy family in this team’

- ‘In this nursery we all agree that there’s nothing wrong in smacking children’

-

Discounting the significance of a situation, for example:

- ‘It’s only a smoker’s cough – everyone gets it’

- ‘Jesse gets the hump sometimes, but that’s just her’

- ‘The odd smack doesn’t do any harm – it didn’t me any harm anyway’

-

Discounting solutions to a problem, for example:

- ‘There’s nothing you can do about stopping smoking’

- ‘We have tried talking to Jesse, but it doesn’t make any difference’

- ‘Sometimes you have no alternative but to smack them’

-

Discounting personal capacity to solve the problem, for example:

- ‘I know there’s a stop smoking clinic but I just can’t spare the time’

- ‘I wouldn’t be able to handle the conflict that would happen if I confronted Jesse’

- ‘We just can’t implement any alternative behaviour management approach’

Also, when we listen to people we can hear how they discount the thinking, feeling or behaviour of themselves or others; ‘I can’t do anything right’, ‘I don’t know’, 'I don’t care’, 'She’s always been stubborn’, ‘He doesn’t understand’

Additional Ideas

There are two other aspects to discounting - grandiosity and passive behaviours

Grandiosity refers to where a colleague makes sweeping, generalising statements about something, for example; ‘Children’s behaviour is far worse nowadays’, ‘Management never listen’, ‘There’s no racism in country areas’

Passive behaviours are quite different. These are four ways in which the individual discounts something about themselves and which is demonstrated in their behaviour. These are behavioural strategies for either getting someone else to solve the problem, or to ensure that it doesn’t get solved at all:

-

Withdrawal

Here the individual either literally withdraws from a situation or metaphorically becomes withdrawn within the group. They do not engage, offer minimal responses and are in most respects absenting themselves from the process. They are discounting their capacity to think and act to resolve the difficulty -

Agitation

In this situation the individual fidgets and fiddles, huffs and puffs, glances around and agitates. They may take apart their pen, doodle on their notes, regularly change their sitting/standing position and generally be unsettled. They are discounting their capacity to say/ask for what they need in order to resolve the difficulty -

Over-adaptation

This is when the individual is overly keen to please others. They may appease when conflict is legitimate, be too swift to offer feedback, too quick to agree and changes position with the to and fro of the group process. They discount their ability to think and act to resolve the difficulty. They may also be discount feelings of anger/resentment. -

Aggression

This is where the individual may be quite literally aggressive, threatening and violent. It may also be obvious by the aggressive defensiveness demonstrated by some individuals. The discount is of the person’s ability to say what they feel and need to resolve the difficulty.

The reason we discount, become grandiose or passive is rooted in our need to maintain a personal sense of normality. From our earliest days we have needed to notice and discount what’s around us in order to create a structure that enables us to survive and make meaning. So, in many respects whilst discounting is invariably unhealthy it is also necessary.

Discounting, Accounting and Peer Mentoring

When we listen to our colleagues it is highly likely that we will pick up on aspects of discounting.

- It may be that the colleague plays down the potential of themself, or runs down the capacity of others or doesn’t pick up something clearly significant in their situation, (or a combination of these).

- It could be that the slip into making grandiose comments about the centres they support or centre/team staff.

- It might be that in the mentoring process they demonstrate a familiar passive behaviour.

There are a number of ways to respond to discounting but the golden rule is to pick up on it – or, to account for the discount. In other words it is important not to discount the discount!

Accounting

Accounting is the opposite of discounting. It means we recognise, notice – stroke – what is being ignored. It can take some practice ad can be met with some resistance, but accounting can be an especially effective way of bringing about a change in relationships and practice.

The routine business of peer discussion can seem to become cumbersome as individuals bring attention to the discount, but the potential for new insights increases. It is also important to understand that simply noticing the discount may not bring about a swift change. Individuals discount to maintain a sense of order/meaning. Therefore there can be a reluctance to acknowledge the discount – which is often made out of awareness.

When we are supporting colleagues instead of colluding with the discount we can respond in a way that accounts at the different levels:

- I can pause the discussion and state that I can see a problem in the situation; ‘I can see that this could be a difficulty’, ‘Tell me how you don’t see a problem developing here'

- I can take responsibility for checking out with myself and the colleague the level of seriousness in the situation. ‘Sounds quite serious – is that how you see it?’ ‘Is there a significance in this situation that I am missing?’

- I can acknowledge that something can be done about the situation. ‘I think that it is right t want to resolve this’, ‘We can devise a solution for this’

- I can encourage both myself and the colleague that we are able to impact on the situation: ‘How might you take this plan forward?’ ‘What would be the most helpful first step?’